Lloyd Corporation

Lloyd Corporation research photograph, The Lanes, Brighton 2020

Lloyd Corporation are an artist duo based in London and Athens. In 2021 they will present a new body of work, Today’s gift is tomorrow’s commodity. Yesterday’s commodity is tomorrow’s found art object. Today’s art object is tomorrow’s junk. And yesterday’s junk is tomorrow’s heirloom, commissioned by Brighton CCA. Below you can find some their ongoing research informing the creation of this new series of art works.

We were in a small flea market shop on The Lanes in Brighton, one of the only ones open on a non-market day and during the early phase of Covid lockdown easing. The shop was overflowing with the usual paraphernalia. Weathered tools from last century’s workshops; Sorry looking Royal Doulton porcelain; unspecified fragments of rusted metal; poor quality kitsch frames; flat-packed furniture worn out as one’s own; a fridge which may or may not belong to the shop owner.

We’ve always drawn to these kinds of places. Where piles of stuff cascade onto one another, a clumsy and ambivalent materiality that doesn’t call out to be seen. Messy and informal with an unruliness to its staging that at least appears to evade composition and discipline. What Jane Bennet calls vibrant matter. One never knows how long these things have actually been there for, placing them somewhere between alive and obsolete, trash or treasure, transient but enduring, trade and collection, commodities or gifts; and back again.

My eyes lingered over this familiar scene and rested upon a wooden barrel. It was casually propped with various bit parts, a plinth for some worn out fold up chairs that almost camouflaged its distinction. The trouble with vibrant matter is that it’s often apprehended en masse, in piles that one sifts through with a kind of distracted attention. What caught my eye about the barrel? Maybe it was the wear of the wood, which captured a sentiment, texture and atmosphere that has always been present in the matters that attract us. Maybe it was the surprising scale of this mundane-familiar-yet-not-really object. Something that we now see as props for the interior décor of public houses or as faux-vintage ornaments in shop spaces. I couldn’t initially put my finger on why I was compelled to take my phone out and capture the barrel. Bringing it into our collaborative dialogue, where images are bounced back and forth leading us in surprising directions. The wooden barrel called out for more attention.

Image from Jamaica Inn, Cornwall

“Though Herodotus mentions palm-wood casks used in shipping Armenian wine to Babylon in Mesopotamia, the barrel as we know it today was most likely developed by the Celts. Around 350 BC they were already using watertight, barrel-shaped wooden containers that were able to withstand stress and could be rolled and stacked. For nearly 2,000 years, barrels were the most convenient form of shipping or storage container for those who could afford them. All kinds of bulk goods, from nails to gold coins, were stored in them.”[i]

The barrel gave us a particular orientation on Brighton’s heritage. The Lanes, where I encountered this barrel, “remain much as they were in the 18th century, when goods were landed on the beach and carried straight up for sale and distribution from shops and inns among the winding alleys and narrow courtyards”.[ii] There are stories of smuggling tunnels that run directly beneath The Lanes, conjuring up myths and legends of dank passages and notorious ‘gentlemen’ rolling barrels of illicit goods to be stashed and transported to London’s black market.

[i] https://www.riverdrive.co/history-of-barrels/

[ii] http://www.smuggling.co.uk/gazetteer_se_18.html

Smugglers at Rye. Original artwork.

“Running round the woodlump if you chance to find

Little barrels, roped and tarred, all full of brandy-wine,

Don’t you shout to come and look, nor use ‘em for your play.

Put the rushwood back again – and they’ll be gone next day!”

Rudyard Kipling, A Smugglers Song, 1906

The economic crisis of the time sparked by Britain’s colonial war in America positioned South Coast towns and villages as hives of resistance to rapid taxation, with import brandy, gin, tea, coffee, salt and spices to quench even ‘the palate of the poor’.[i] Evidently the history of smuggling still has a grip in Brighton and across the south coast, as an object of heritage, folklore and branding. One can go on a walking tour of the Smugglers Tunnels and Myths & Legends of New Brighton. Stop for a pint at The Smugglers pub on Ship Street or a meal at The Smugglers Rest. If you’re a local resident become a member of Rottingdean Smugglers, a society that holds annual torch lit parades, “an edgy, noisy, fantastical evening … of fire, drumming, costume, fireworks and seasonal fayre. A hybrid night of noise and mayhem.”[ii]

FILM: Rottingdean Smugglers 2016 from Zak Thorpe on Vimeo.

This fits into a rich vein of south coast traditions dating back to ambiguous origins and steeped in period aesthetics of burning effigies and fireworks. Lewes Bonfire Night Celebrations might have started with the failed Gunpowder Plot in 1605, the commemoration of 17 Protestant martyrs burned at stake during the Reformation, or to warn of the advances of the Spanish Armada.[iii] In Ottery St Mary the Gunpowder Plot is similarly mythologised through an age-old tradition of local families carrying lighted Tar Barrels through crowded streets.[iv] These traditions are now increasingly visible, sought after, consumed in Guardian picture galleries, attracting numbers that burst the seams of narrow town streets. As shared myths and public rituals, they continue to provide a space for contemporary carnival – a rare outlet for eccentricity, impromptu commoning and political dissent to take centre stage.

“It would seem that mythological worlds have been built up only to be shattered again, and that new worlds were built from the fragments.”

Franz Boas, I898

[i] The Complete English Tradesman, Vol. 2, Page 91 Daniel Defoe, 1727

[ii] http://www.rottingdeansmugglers.co.uk/about/

[iii] https://www.lewesbonfirecelebrations.com/article/lewes-bonfire-origins/

[iv] https://www.devonlive.com/whats-on/whats-on-news/mysterious-history-ottery-tar-barrels-2177960

FILM: Bonfire at Lewes, 1974

FILM: The Flaming Tar Barrels of Ottery St Mary, Courtesy BFI Player.

What about the barrel itself? Weathered, stained, rusted, grained, graded. Should we ask where it came from? How it ended up there, in amongst the ad hoc paraphernalia of flea market wares? What its journey or circulations were? What it held as a vessel or how it was held as a possession with a certain role or value? Who made it and where? How was it gripped, cut, shaped, sanded, fired, bent, bound, rolled, packed, exchanged, emptied, disposed? How many others were crafted by these hands? What other hands held it and when and why? Would knowing any of this get us closer to knowing the barrel? Are we even concerned with this barrel specifically?

“The idea of the thing itself is a way to capture the stubbornness of the materiality of things, which is also connected to their profusion, their resistance to strict measures of equivalence, and to strict distinctions between the maker and the made, the gift and the commodity, the work of art and the objects of everyday life… the magic of materiality and the unruliness of the world of things. This unruliness thrives on the ephemerality of the artwork, the plenitude of material life, the multiple forms and futures that the social life of things can take, and the hazy borders between things and the persons whose social life they enrich and complicate.”

Arjun Appadurai, 2006

Solid Wooden Oak Whiskey Barrels, 55 Gallons (250 Litres), Ebay.co.uk

Now we talk about barrels. We find more and more of them and share images over Whatsapp messages. Barrels are everywhere. Plastered with promotional stickers and propping up flowerpots in a small pub in Brixton. Sandwiched between three metal stools as a dining station on the promenade of the port town of La Ciotat on the South Coast of France. Presented in large stacks on a thumbnail image advertising the television and film prop company Keeley Hire Ltd. Multiplying as pop ups whenever we open up webpages. A good friend of ours stands inside a barrel strapped over his shoulders as a costume in an old photograph. The contexts and narratives are expanding.

Still from Five Weeks Up The Pole? 1966, Birmingham, British Pathe

Lloyd Corporation research photograph 2020

“If you were an unemployed colonial who wished to learn a trade that guaranteed work, enough to give your family a decent livelihood, then learning the trade of cooper was the way to go.”[i]

It was somehow surprising to discover that the Cooper trade was the biggest artisan profession during the 17th and 18th century in the West. The Worshipful Company of Cooper’s based in the City of London suggests “origins lost in the mists of time but tracing descent back to 12th century medieval Trade Guilds”. The authority of the guild, to impose regulation and control on the production of barrels, conferred significant power and wealth as the demand for vessels rose with the expansion of sea trade and empire. When encountered in pub gardens propping up pint glasses, it’s easy to ignore the quiet legacies and social histories of these benign looking objects. Barrels as a primary technology of empire, instrumental in the vast extraction of resources and expansion of capitalist exploitation across the globe. The violence and deep traumas of transatlantic slavery and the enduring legacies of inequality, displacement and racism that persist in those societies that ‘developed’ from empire’s extractions.

[i] http://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/coopers-had-the-colonists-over-a-barrel-18th-century-barrel-cask-production-in-america/

A cooper making a barrel, Netherlands. From a Dutch woodcut of the 16th century. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

FILM: Brian Palfrey, Cooper. Courtesy BFI Player.

“The idea of a social life of things addresses the interactions between human beings and the material world in a way that pays particular attention to the specific reactions elicited by objects. This reflexive relationship in which the existence of people is responsible for the creation of objects and objects are responsible for the creation of the particularities of human existence”[i]

The sociologist Caroline Knowles traces the object biography of a pair of plastic flip flops, “unpacking the lives and landscapes hidden in the plastic” (Knowles, 2015). The Flip Flop Trail is both a sociological and political endeavour. To expand the vantage points from which we might comprehend the vast abstraction that is globalisation by drawing us into intricate stories from the perspective of a plastic shoe. Humanising supply chain geographies by following the lives and bodies of its wearers and the trails they walk. We start in Kuwait, with the daily routines of a geologist, a landscape of oil extraction and the citizens it makes. On an oil tanker we reach South Korea and the corporate word of multinationals processing raw plastic materials. Manufacturing in China or increasingly Vietnam. Distribution to and through Somalia, Djibouti, Ethiopia.

On reaching ‘globalisations backroads’, a pair of flip flops protecting the feet of a precarious, elderly women who walks miles each day to vend food on the streets of Addis Ababa. Worn out, repaired and finally disposed in landfill to sit dormant for hundreds of years. “From the vantage point of the flipflop trail, globalization looks rather different. It is more fragile and shifting, generating multiple forms of uncertainty in the lives and landscapes it simultaneously sustains and undermines.” (Knowles, 2015)

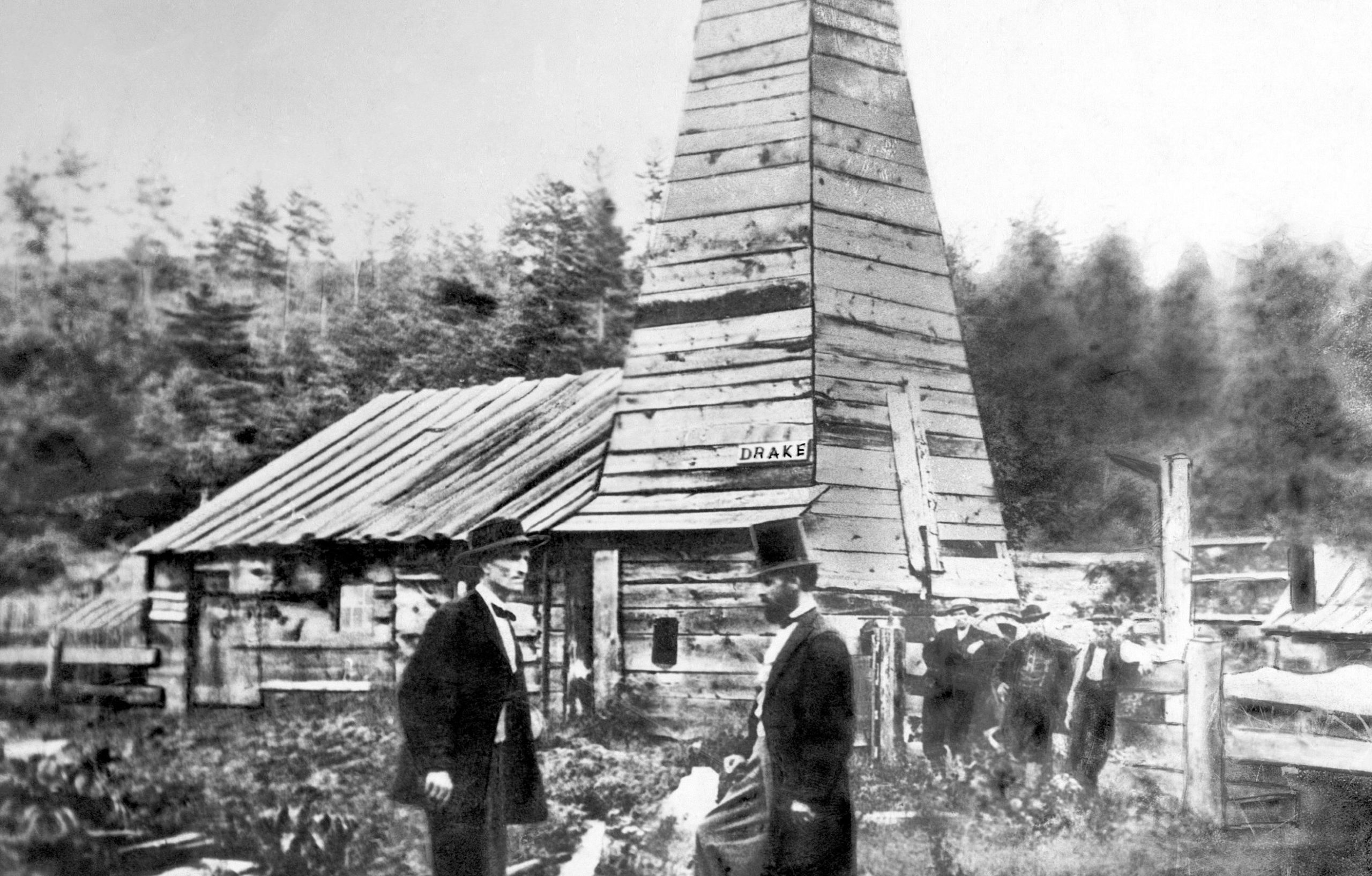

It’s commonplace to talk about a ‘barrel of oil’ even though they are no longer used as the physical container for much of the worlds transport. The 42 US-gallon oil barrel is a unit of measure, an abstraction removed from its material origins in the early Pennsylvania oil fields. “The Drake Well, the first oil well in the US, was drilled in Pennsylvania in 1859, and an oil boom followed in the 1860s. When oil production began, there was no standard container for oil, so oil and petroleum products were stored and transported in barrels of different shapes and sizes. Some of these barrels would originally have been used for other products, such as beer, fish, molasses, or turpentine.”[ii]

[i] Diana Fridberg, The Social Life of Things, 2008, Created as part of the SMU Theory Project

[ii] https://aoghs.org/transportation/history-of-the-42-gallon-oil-barrel/

Photograph of Col. Edwin L. Drake (right) and Peter Wilson (left) standing in front of the engine house and derrick of the Drake Well, 1866 (image from Drake Well Museum and Park)

Nowadays oil pipelines run like networks of arteries carving through miles of seemingly barren landscape, connecting global sites of production with their corporate state interests. However, these are not the only markets. The former proto-state created by ISIL was funded by illicit oil distributed in barrels of all shapes and sizes and smuggled from captured fields in the Syria and Iraq.

Can a Dead Cat Bounce? Inside thinking of Kinder Morgan on its gas pipeline proposal (image from 350MA)

This Is How ISIS Smuggles Oil (image from BuzzFeed News)

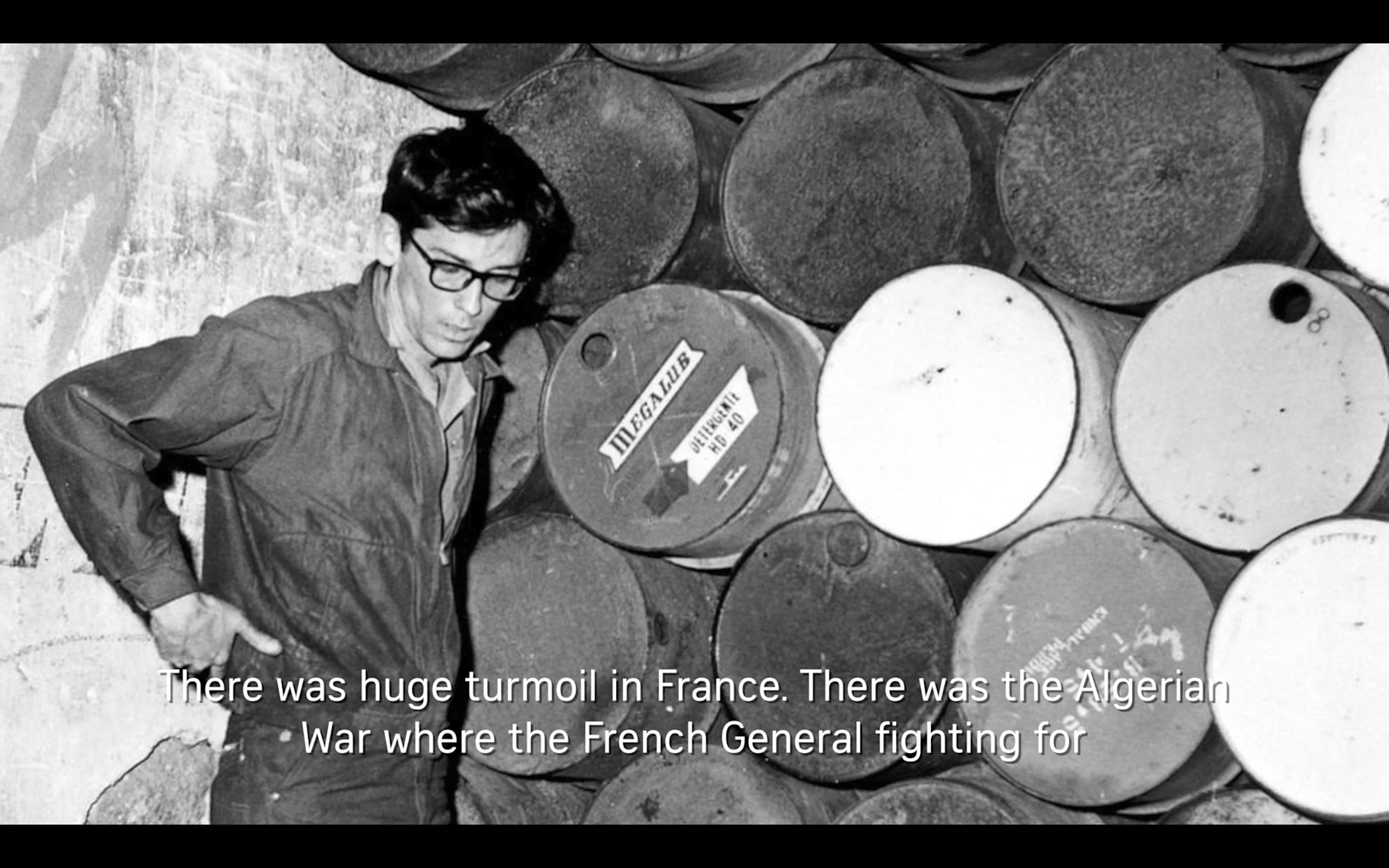

These slippery relationships of barrels and oil – between material and measure, resource and property, wealth and violence – is possibly what so intrigued artists Christo and Jean Claude in their use of these objects throughout their career. Barrels were used to create an Iron Curtain blockading the Rue Visconti in Paris, a public intervention as mirror to the divisions and disorder resisting France’s colonial suppression of Algerian independence.

Still from Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Barrels and The Mastaba 1958–2018 (image from Serpentine Galleries)

More speculative yet is their ambitious project for the creation of an oil barrel Mastaba in the United Arab Emirates, conceived over 40 years ago and still to be realised (now posthumously). Proposed as the largest sculpture in the world it would feature 410,000 colourfully painted barrels in the form of an ancient Egyptian tomb. One can’t help imagine these barrels as corpses building the blocks of their own burial ground. A perverse, symbolic commentary on the finitude of a political economy that the IMF has predicted, even before coronavirus struck, would exhaust its $2trillion reserves by 2034.[i]

[i] https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2020/07/18/the-end-of-the-arab-worlds-oil-age-is-nigh

First scale model test at the proposed site of The Mastaba, November 2011, Photo: Wolfgang Volz © 2011 Christo (image from Christo and Jean Claude)

Barrels have been direct vessels of both violence and resistance. Although reportedly used throughout the 20th century, the barrel bomb has come to global attention through their use by Bashar Al Assad’s regime during the Syrian civil war. Campaign groups including Amnesty International have produced evidence of the sheer destruction and tragedy of these weapons. Diagrams show the fabrication of these devices and make painfully visible how the barrel itself becomes a deadly shell packed with steel bar and TNT explosives.[i] Their indiscriminate use has been responsible for a substantial part of the hundreds of thousands of deaths from airstrikes during the conflict.

[i] https://www.amnesty.org.uk/circle-hell-barrel-bombs-aleppo-syria

A fake barrel bomb being installed in the museum, Andrew Tunnard/IWM (image from The Times)

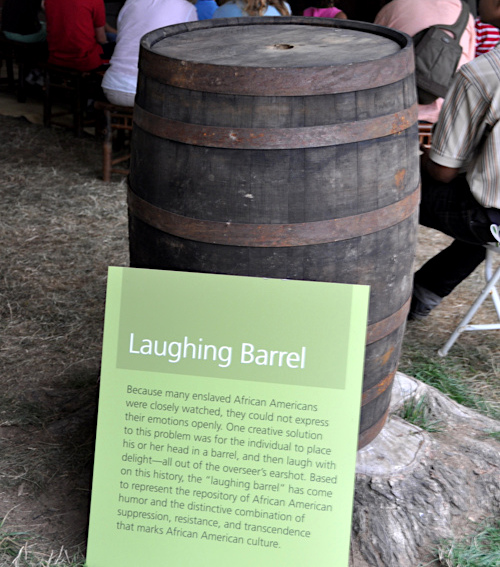

Conversely the hollow interior of barrels became a site of resistance for African American plantation slaves. It is said that individuals would place their heads inside to hide their laughter from overseers, who would punish any expressions of emotions. “The “laughing barrel” has come to represent the repository of African American humour and the distinctive combination of suppression, resistance, and transcendence that marks African American culture.”[i]

[i] http://blackyouthproject.com/laughing-barrels-and-the-defiant-spirit-of-black-laughter/

“Laughing barrels” and the defiant spirit of Black laughter (image from the Black Youth Project)

Now it’s possible to buy old wooden barrels online, even if they still have a soaring currency in the worlds of the whisky and wine brewing. “Barrels used for maturing bourbon are required by American law to be made from American white oak which has been charred prior to usage. As these casks cannot be re-used to make bourbon, they experience a second life maturing Scotch Whisky.”[i] Then an after-life in the upcycle economy recirculating barrels as garden planters or landscape features.

[i] https://whisky-barrels.co.uk/product/american-standard-barrel/#:~:text=Also%20known%20as%20the%20ASB,been%20charred%20prior%20to%20usage.

Lloyd Corporation research Research Photograph, Dole, France

Image courtesy of Amazon.com

Now we’ve begun to ask ourselves: What other ways might these old barrels be recycled and reclaimed? What would it look like to ‘re-cooperate’ barrels? To re-make them as sites of social research, artistic practice and critical discourse. What biographies and social histories of barrels could be weaved together? To re-new barrels as vessels – not for beer, wine, rum, flour or cotton – but for carrying traces of empire, trade, heritage and myth. Where would a barrel-trail lead us and what lives and landscapes would it bring to the surface?